The Satrap in Yellow

A cosmic horror adventure tale set in the time of Alexander the Great

There are four truths that I know. I know these truths, as I have seen them with my own eyes, felt them shake my soul to its very core. Many are the hours I have dreamt I could un-know these truths, that I could un-see the things I have seen, and go back to my simple life in that dreary fishing village on the Cimmerian shore. I dream that I could go back to a time before I ever listened to the stories the old Scythian man told of conquest and adventure, before I ever heard the name of Alexander of Macedon.

The first of these truths is that everything that exists, all that is real, from the smallest grain of sand beneath my feet, to the farthest star in the night sky, far beyond the eyes of men, is of Grace. All that is, all that was, and all that will be, is of Grace.

The second is much less comforting. It is the truth that our world, our reality, is not all that there is, and that beyond it, exists a place of madness, a timeless oblivion of horror and fear, populated by an infinite number of foul aberrations, screaming in demented rage with hate for all that is order, for all that is of Grace.

The third truth is the worst of all, that a gateway, a door, can be opened, however briefly, between that world, and ours. No spell or incantation, no ritual or ancient scroll may open it. The way to open such a doorway, to tear a hole in reality itself, and make flesh those unspeakable abominations that dwell there, is so horrifying that to attempt a simple explanation is to flirt with madness.

The fourth truth, and the one that has guided my life from the moment that I knew it, the one truth that keeps my mind from simply slipping away after the things that I have seen, is that all that is of Grace, is protected by Grace. It is that She is always there, our Mother, as She has been, as long as tales were told. Her likeness spread round the world, before the time of beast and plow, before the first smith’s hammer ever fell, She was there. And, most importantly, her children were there. The children of M’tta, those blessed Children of Grace, whom I serve.

It was the old Scythian man’s fault, I had decided, as I found myself floating in the Great Sea off the Axum coast. The tales of adventure he had told me as a youth had led me here. The little boat I had stolen sailed true, but its boards, unbeknownst to me, were in dire need of shoring. It was a trusty vessel, which took me all the way to the place where it sank. At least a few of the boards drifted free, as the rest of the hull, along with my axe and a perfectly good Massagetae bow, sank past my sight.

At least, I thought, I would die at sea, like my father, and not in one of the horrible ways I had witnessed in that place where no sane man dared tread. Even to be eaten by sharks would be a kinder death than that. My strength depleted, I resolved that my tasks were finished, and that I had done my best to fulfill my oath. I slumped across the remains of my vessel, awaiting death.

I do not know how much time passed from the moment the candle of consciousness went out, to the time that I awoke on the deck of the Anki, a cool wet cloth stretched above me for shade. A young girl sat next to me, tending to me, and sprang from my side as I stirred for what must have been the first time in days.

The Anki was not a large ship, not the gaudy naval galleys of the Greeks or Persians. It was elegant and nimble, the ship of a trader, or of a pirate. I would discover, in time, that the Anki was both, and neither.

I rested for the next few days, as my strength recovered, keeping a wary eye on my new caretakers. After what I had seen, I trusted no one. But still, I felt the overwhelming urge to tell them, to warn all of humanity of the thing that had been awakened on that grassy plain, that place where stood that awful figure of stone.

In time, I was able to speak, and while wary, I could not keep the horrors inside my mind to myself any longer. I asked to speak to the master of the crew of the Anki, their captain, the man called Ashur. Someone must know.

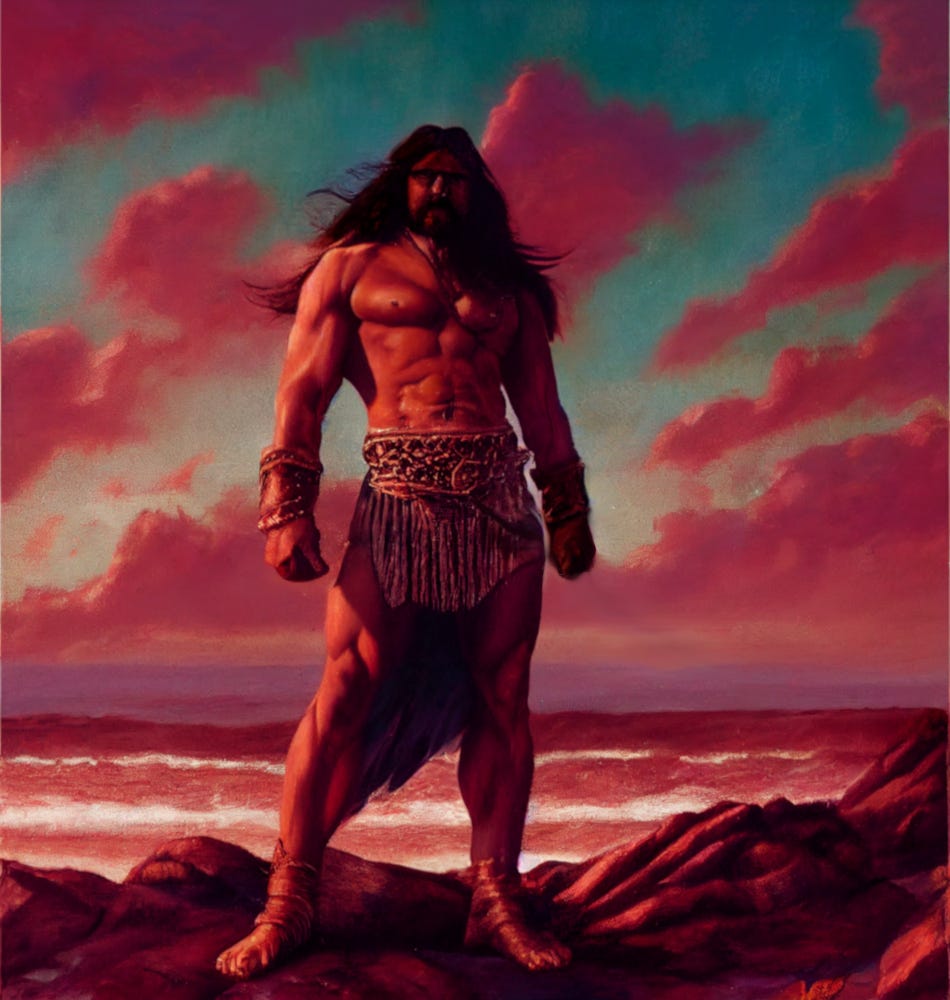

Not the tallest of the crew, or the strongest, and yet somehow possessed with the spirit of a giant, Ashur seemed to command respect from the very air around him. His crew practically worshiped him, when they weren’t drinking and laughing with him. He was sharply muscled, made clear by the fact that he never seemed to wear a shirt or tunic, only clothing himself in loose trousers that ended well above his sandaled feet. His hair was long, and black as pitch, as was his beard.

Ashur’s deep blue eyes seemed to glow, contrasted with his olive skin, as he sat down on the deck beneath the shade of the Anki’s sails. I was anxious, afraid to speak the words, afraid that telling the tale would make it all real once more, but something about this man, the strength of his voice, gave me a strange calm.

“You have something to say,” Ashur said, “I can see it in your eyes, I could see it when we found you. Your story is more than just another shipwreck, isn’t it?” His blue eyes stared into my soul. “My crew and I, we have seen much of this world, and of those things beyond it. You are safe here.”

I let out a sigh, and began my tale.

I had served Alexander for sixteen months when we met the Satrap. My brothers and I were suspicious from the start, though our master seemed to grow closer to the yellow-robed foreign devil with each passing week. My king had many such Satraps, some of Greek blood, some Asian, some local tribal leaders, puppet rulers left in place after our forces departed.

Musarra, the man called himself, as he threw himself at Alexander’s feet, while his slaves brought in bags of silver and jewels. The Guardian and Prince of Carcosa, he told our king, as he swore his fealty to the conqueror. Alexander seemed to instantly take to the prince, nodding along with every word Musarra spoke as he turned over a square Carcosan coin in his hand and gazed at the strange symbol upon its face.

My brothers and I, sworn to protect our master, watched Musarra as a hungry cat watches a bird. It wasn’t long until our greatest suspicions were realized, and we discovered Musarra for whatever he, or it, was. I saw it myself, the tall yellow-robed prince standing next to our king, as his shadow moved on its own, and whispered into Alexander’s ear.

We resolved, and swore, the four of us who were there that night, to kill Musarra, before he could further cloud our master’s mind. It seemed the gods had heard our oath when Alexander declared Musarra the Satrap of Carcosa, a land of which none of us had ever heard. Musarra had convinced Alexander that he needed help in securing his kingdom from his rivals, and in exchange, Carcosa would become another province of Alexander. At least, we thought, as a Satrap of a distant province, Musarra could no longer whisper his foul magic into Alexander’s ear.

We volunteered for the expedition. We could kill the demon on the road. If only Ptolemy or Hephaestion had been there to sway our king’s mind back to sanity, we could have ended the foul prince right then and there. It was only luck, or the gods, who kept Alexander from going along to Carcosa with us. The King suffered one of his spells, a severe one, and could not travel. Musarra protested, almost insisting that Alexander join us. Finally, he reluctantly obeyed the King’s order, and set forth south from Egypt with two-thousand Macedonian regulars, and mercenaries like myself and my brothers. It was insanity, but it was our king’s command.

We crossed through the kingdom of Axum, where our general sent scouts toward the walled city to gauge its defenses. We would give the city a wide berth, if need be, as we tracked south to the land of Musarra. Our scouts found the city abandoned, with tracks of hundreds, perhaps thousands, heading out in all directions, save one. No tracks led south toward Carcosa.

Days later, Musarra declared that we had passed into his land, as we crossed a muddy ford of a river, unsurprisingly called the Yellow. What path there had been slowly vanished, and we were all left following the yellow prince, our entire force at his back, gazing at the strange symbol that adorned his banners. Another day’s march, and my brothers and I, near the head of our force, spotted an object in the distance. Excitement began to circulate among the troops, the anticipation of a city on the horizon.

There was no city. There was nothing in our path but a massive stone figure, a pile of rock fashioned in the shape of a man, or a beast, standing alone on a grassy plain. Musarra explained that it was one of the gods of Carcosa, a guardian of the dead. It was a reasonable explanation, as the tall grass was littered with bones. We all believed him, all of us, to a man, even myself and my brothers. Our distrust of the yellow Satrap had faded, and we trusted him as Alexander did.

We camped there, at the feet of the stone giant, among the rotting bones. Though it was a thing that no man of our company would have done before that day, we would sleep that night in a burial ground. Our superstitions were gone, as our minds were soon to follow.

The morning came quickly as all our company shed their armor, and left their swords lying in the grass. It did not seem strange at all that our general walked the camp naked, offering to lie with any man who felt so inclined. All the wine, all the food we had brought, was broken open and torn through, as men began to behave like animals, eating, drinking, copulating like beasts.

Fights followed. Depravity followed. A few of our company actually drank themselves to death, as the rest of us looked on and laughed. Hands found swords, and blood was spilled for amusement. I was no exception, and was only saved by chance, as I searched for a cloth to clean the blood from the sword I had just used to kill one of my own.

I was delighted when instead, I found my deadly war hammer. As I grasped it, my sanity came rushing back to me, and I realized what was happening. I did the only thing I could think to do, as I witnessed the growing madness around me, and ran for the treeline. Unfortunately, I was spotted by an insane woman, and the two men who followed her. I ran as fast as I could, and luckily, the two men became distracted when the woman fell, and they piled onto her, fighting viciously over which would take her first, until one of them stood, his throat ripped out. He smiled at me, as blood gushed from his mouth, and fell down dead.

The hammer had saved me, somehow, from the insanity of the Carcosan field of bones. The old Scythian hermit had given it to me, before I left to join up with Alexander. He said it was sacred, and would protect me, claiming that it was a relic of the ancient abandoned monastery where he lived. He said it was found in a sacred circle of stones, outside in the courtyard. It was bronze, with a cast image on its head, the same image that adorned everything he had found there, that of a goddess, a plump woman with large breasts and swollen belly. The image of the Mother.

Even though I possessed some sort of powerful talisman, I was still helpless, hiding among the trees, watching our entire force mangle and kill each other as the sun began to set behind the stone figure. Musarra stood beneath the stone, watching the chaos ensue, waving his hands about, making strange incantations, speaking poisonous words. I realized, as the sun faded, and the shadow of the stone thing grew long, that the yellow prince cast no shadow at all.

Then I saw it. His shadow did exist. It moved through the camp, laying its foul hand on every man it passed, whispering to them, seducing them. I saw its face. It was not the same face as Musarra. Black slime seemed to drip from its mouth, and two dark voids sat where eyes should have been, and another larger emptiness I could see in the middle of its head. It crawled, slithered, and stumbled its way along, spreading chaos as it went.

Musarra held up his foul hands, which almost resembled the arms of a squid, and yelled in his putrid tongue, so loudly that I can almost hear it now. The madness stopped, but for a moment, as men were grabbed up by the crowd, and dragged to the feet of the stone idol.

What happened to those men is a thing that will haunt my dreams until I go to my rest. It was not a thing I was aware could even be done to a man, not without death. In time, various pieces, skins, organs, entrails of those poor devils were passed about the crowd, but somehow, they yet lived, screaming in anguish and disbelief, their sanity returned to them like a cruel joke. There must have been a hundred of them there by the time the horror appeared, I can still see them, still hear their screams. Even now, the stench of that horrible night fills my nostrils if I let it.

I wondered if I could end myself, if I could claw open my own wrists, or stab the spike of my hammer through my heart. I could not imagine going on after what I had seen. At that point, I only survived because I was utterly paralyzed with fear.

Then, it appeared. Something greenish yellow, at first just a mass of gore beneath the stone figure, began to take shape, though it was still too terrible to describe. It was a thing of tooth and claw and horn, of flesh and rock and metal. It slipped from between the stone figure’s legs, as if the statue was giving birth or defecating. It grew larger, screaming and writhing, until it was as big as the stone idol itself. Like the yellow Satrap, and his crawling shadow, it was not of this world. My heart raced at the sight of it, and then fell calm, as I was given the sweet gift of darkness, my shattered mind simply snuffing out the light.

I awoke the next morning to silence. Though the sun gave me some comfort, I lay still for hours, afraid to move, afraid that the thing may still be there. When at last my courage found me, I raced away from the place that had been our camp, and did not look back. If any of our company yet lived, they would not find aid from me. I would find my way back to the Black Sea, and return my hammer to its home, and myself to mine.

My fear turned to rage, when I saw the tent of Musarra, saw his slaves serving his breakfast, as he relaxed on a cushion in the shade. Two thousand men, my companions, my brothers, had been taken by the yellow monster’s madness, sacrificed to raise that unspeakable thing. Musarra would die.

I crept past his tent, as quiet as a viper, and dispatched his guards, one by one, with the bronze hammer, as my hate brought back my courage. I took a bow from one of the dead, and one arrow. It was all I would need. I slipped quietly around to the tent, and nocked my arrow carefully. I should have been more discriminating in my choice of arrows, as one of the feathers flew off as I loosed it at Musarra. It struck him, but only in the shoulder, and he screamed an unholy scream at me, his eyes turned to pools of sickly yellowish green.

I charged at him with my hammer, but was stopped by his servants, as the Satrap ran for his putrid life. His shadow deserted him, and dashed screaming through the brush. For whatever reason, they both seemed to fear me. I fought with Musarra’s slaves, killing one with the hammer, at which point they all fled as well.

I turned to hear the sound of hoof-beats, and to see the yellow-robed figure escaping, whipping his mount frantically as he vanished over a small hill. He was mine now. I calmly walked over to the tent, and ate the remainder of the bastard’s breakfast. Then I chose one of the horses, and found a better bow, and a quiver of true arrows.

I rode out, following the clumsy trail Musarra had left for me, until I spotted him, climbing sloppily up a hillside. He spotted me as well, and whipped his horse hard. It would do him no good. I kicked my steed forward, and in a moment, we had crossed over the hill, and were riding across another grassy plain. I rode my mount at full gallop, something my prey could not do. I had noted it on the way down to Carcosa, that Musarra was a terrible rider, as rich men often were.

I was closing in. My quarry spurred his horse harder, almost falling from the saddle, riding like mad for the brush at the edge of the grassland. He paused as he reached it, and turned to face a surprise, as the first of my arrows found his chest. Two more followed, before he could even fall from his horse. The old Scythian man had not just told me stories, he had served as a sort of father to me, and had taught me the skills that made me Alexander’s best horse archer.

Lions were on Musarra’s corpse before I could even reach him. I watched them tear his body to shreds. I waited until they had their fill, and collected the Satrap’s head, a small gift of consolation for my king. I rode for the coast, hoping to cross the sea, and rejoin my master somewhere to the east, knowing he had surely left Egypt by that time.

“My boat sank, as you know, and that is how I came to be here,” I said, concluding my story.

Ashur looked about the ship, as he rubbed his hairy jaw.

“My lord Anun,” a stout man of the crew said to him, “should we stay our course?”

It seemed something I said prompted the question. I barely heard it, as I was dumbstruck by the tattoo on the sailor’s arm. It was the image of the Mother, the same as the one on my now lost war hammer.

“Of course!” Ashur (or Anun) laughed, “we should go and see this Carcosa for ourselves!” He almost fell onto the deck laughing.

I sat there, dumbfounded. Did he think it was all just a tale? I shuddered at the thought of returning to that field of bones.

“Please, Captain…” I began to speak.

“Do not worry, brave lad,” Ashur said, “you have done well. You have saved your king, and perhaps thousands more, from that abomination. You’ve snuffed out its flame, for now. I don’t think a mortal man has done that since… well, I don’t know when.” He laughed, and put his strong hand on my shoulder.

Mortal man? I did not understand. For now? Would Musarra somehow return?

“Sorry to disappoint, lad,” Ashur said, “he will be reborn. He always comes back. Next time we’ll be more prepared. Yellow robes… such an arrogant fool. I so wish his head not been lost, it would have made a fine decoration.” He pointed to the prow of the Anki.

“Lord Ashur, or Anun, or…” I spoke. “If you wish to go to Carcosa, I will point the way, but that is all. I am grateful to you for saving me, but I must…”

“Oh, come now lad,” he said, “wouldn’t you like to see that thing among the rocks ended, as you ended the yellow king?” Something in his tone was soothing, and somehow inspiring at the same time.

“Those who serve me call me Lord Anun,” he said. “Any man who has slain that yellow-clad menace may simply call me Anun, and count me among his friends.”

Less than a day later, the Anki reached the shore, south of Axum. My courage somewhat returned, I reluctantly led Anun and his men as best as I could toward the field of bones. I thought, and hoped, that I had lost it, and that we may not find that place, until the smell of rotting flesh reached our nostrils, and we knew we were growing close.

We stopped just short of that place, where we could see the top of the stone figure rising above the brush. Packs were shed. Swords were drawn, spears and shields made ready.

“Keep quiet, lads,” Anun said to us all, “remember, there’s a behemoth out there, and it sounds like a fast one. Stand together, and stand fast. If we are able, we’ll pin it against the rock.” The crew nodded.

“Grace be with you,” Anun whispered. His men repeated his words.

I followed them to the edge of the plain, and there I stopped. The crew began to move carefully toward the stone idol, in a tight formation, swords and spears at the ready.

“Can you climb?” Anun asked me, as he looked up the trunk of a stout tree. I nodded, though I was still at the edge of panic just being in this place littered with the corpses of my former companions. Every fiber of me wanted to run. I began to wonder if I could reach the ship, and sail the Anki on my own, without her crew.

“Then take this,” Anun said, handing me the most elegant bow I had ever seen, and a quiver of perfect arrows. “Aim for the eyes, if it has any.”

Anun stalked away, his head down, his shoulders up, like a wolf stalking its prey. He drew a large curved sword from a leather scabbard, and clenched its ivory handle tightly in his hand, as he dropped the scabbard in the grass.

His men stopped, just short of the stone idol, and crouched down in the tall grass, shields together, as if forming a wall. Anun walked silently toward the figure of rock, and struck it with the great sword, so hard that I was certain the blade must have shattered. It did not. The statue shook, slightly, and began to lean backwards, as an ear-splitting sound rang across the plain. PRAANNGGG!!

There was another sound, a sound like metal scraping, like goats screaming, like hail on a clay roof, blood-curdling and unnatural. The behemoth sprang forward from among the rocks, still an indescribable form, like a column of flesh, with sharp edges and claws and teeth. It had no head, but had many mouths, gaping chasms of bone-crushing death. I was sure that I was about to watch my new companions die, as I had before, and end up here alone with that thing once again.

It lurched at Anun, but he was fast, unnaturally fast, and dodged the attack, striking a blow with the bronze sword as he did. The thing let out an even louder scream, and turned to flee from Anun’s blade, only to rush headlong into the wall of shields and spears. It whirled again, insanely, and fixed the largest of its many eyes again upon Lord Anun.

It howled and thrashed, as my arrow found that largest eye. My courage had returned once again, but stronger. I had not even found my true courage until that day on the Carcosan field of death. This thing, this trespasser, would not live to serve whatever purpose for which Musarra had raised it. It would die here, as my brothers had died.

The spears of Anun’s men pushed the thing, forcing it against the rocks, as I put a second arrow through another of its sickly yellow eyes. I drew my bow, and loosed yet another into its largest eye, which appeared to be healing, growing, regenerating. The arrows, swords, and spears could not render lasting damage to the cursed thing. It would not matter.

The sun was sinking, as I caught site of the silhouette of Lord Anun, standing defiantly atop the leaning stone figure. He leapt from the rock as a leopard would bound from a limb, and fell upon the behemoth monstrosity with the swiftness of an arrow. The great sword cut deep into the putrid flesh of the thing, as Anun’s men closed in on it, slashing and jabbing at it, as their master sliced its flesh as cleanly as a butcher would slice a slaughtered pig.

I loosed the rest of my arrows, in rapid succession, into the beast, as the very air around me seemed to ring with victory. I do not recall clearly the events that followed, only that when it was over, nothing at all remained of that foul thing, not even ash.

We did celebrate, for a short time, and passed a flask of strong mead, as Anun entertained us with a lewd ancient poem about a sea monster and a woman with three breasts. However, we soon retreated to a hilltop, back among the trees, to camp for the night. We would not be foolish enough to camp on that field of bones, beneath that stone idol. We kept a wary watch that night, as every unidentified shadow of the firelight made me shudder, wondering where that other thing, Musarra’s shadow, that dark, creeping, crawling chaos might have gone.

The next morning, we returned to the field, and tore down that figure of rock, leaving a great pile of stones to mark the graveyard of my former brothers. We lit the grass as we left, and the entire plain became a pier for the unfortunate souls that perished there in madness. Anun knelt by the edge of the forest, leaning on the great sword, and whispered a quiet prayer.

He would teach me that prayer, eventually. My lord Anun would teach me many things, and I would come to know the light of Grace, as he told me the story of the beginning, and of our Mother. I came to serve him, and his kin, and he anointed me as one of his knights, there on the deck of the Anki, where I was rescued, where I was reborn.

Many years have passed since that day, and I have lived many adventures in the service of my lord. I serve him still. He is Anun, the Wolf of Sumeria, the slayer of the tyrant Cyrus, master of the Anki, father of nations, Child of Grace. My oldest friend. One would not know it to look at us, as the years have seen me grow tired and gray, but he remains, the same as that day we met.

It is in service to him, and by my own personal request, that I find myself in this strange city, far from my home, standing in the market at dusk, pretending to belong here. A jeweled nobleman and his attendants pass by quickly, and I carefully turn to follow. I do not care for cities, it is too difficult to wield a bow, or even a decent sword in a crowded stinking trash heap like this one.

It would be more pleasing, and a bit poetic, if they took to horseback, and I could cut them down out in the open. My short sword will have to suffice. I follow them carefully, until they turn and enter a tavern, or whatever passes for a tavern in this foreign place. I quickly make friends with the young noble, buying drinks, spreading my gold around, trying my best to tell that lewd Sumerian tale about the sea monster and the woman with three breasts, in their garbled, senseless tongue. Night falls, and so do his attendants, one by one, to the poison I gave them in that putrid swill that is called wine in this land.

At last, only the two of us remain awake at the dark table, the nobleman and I, as I ask him to help me pronounce his name. He laughs at me as I struggle to say it, amused as he carelessly fondles his yellow scarf in his hands.

“Musarra,” I say, “is it pronounced, Musarra?” I glance down at my left hand, and back at him. His eyes fix to the small tattoo across the back of my hand, a worn image of a running wolf. I turn over my hand, exposing the tattoo of the Mother on my palm. He shakes. His eyes grow wide, and stare at mine in horror and disbelief.

I smile. That yellow scarf will be quite handy for cleaning the blood from my blade.